- Home

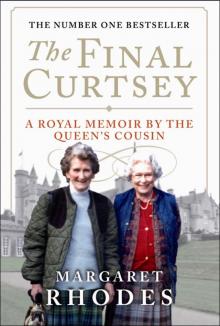

- Margaret Rhodes

The Final Curtsey

The Final Curtsey Read online

Margaret Rhodes was born into a now almost vanished world of privilege. Royalty often came to stay, and every summer she holidayed with Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret at Balmoral. The three cousins were virtually brought up together, and her aunt Queen Elizabeth regarded her as ‘my third daughter’.

The Second World War years were spent in Scotland, Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace, where the author ‘lodged’ while she worked for MI6. She celebrated VE day and VJ day with the princesses, mingling in the streets with the wildly celebrating crowds. She was a bridesmaid at the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, and three years later married Denys Rhodes, a grandson of the 5th Lord Plunket. The King and Queen attended the wedding, and Princess Margaret was a bridesmaid. Four children and a life of adventure and exploration followed.

Her home was in Devon, but in 1980, when Denys became seriously ill, the Queen offered them a house in the Great Park at Windsor, asking whether they could ‘bear to live in suburbia’. Margaret Rhodes lives there still, her routine punctuated by regular visits to Balmoral and Sandringham. In 1990 she was appointed as a Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen Mother, acting also as her companion, and was at her bedside when she died at Easter 2002.

The author as a bridesmaid to Princess Elizabeth, November 1947

Published jointly by Birlinn Ltd

and Umbria Press 2012

Copyright © Margaret Rhodes 2012

Margaret Rhodes has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

Umbria Press,

2 Umbria Street,

London SW15 5DP

ISBN: 978 1 78027 085 2

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 191 0

Version 1.1

I would like to dedicate this book to the memories of my much loved aunt, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, as well as to my darling husband Denys.

I would like to thank Tom Corby, the former Press Association Court Correspondent, who convinced me that there was a book in me. He had faith in the book from the outset.

I am most grateful to Alan Gordon Walker, of Umbria Press, who has provided me with support and helpful advice and guided me in bringing the book to fruition.

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1 The Final Curtsey

Chapter 2 Upstairs and Downstairs

Chapter 3 Wartime with the Windsors

Chapter 4 Secret Army

Chapter 5 Love and Marriage

Chapter 6 On Top of the World

Chapter 7 African Adventure

Chapter 8 In-Waiting

Chapter 9 Afterwards

Foreword

People have told me that I have become a publishing sensation, which I take with a large pinch of salt. Frankly I’m amazed that so many people have become interested in my life and times, and I firmly believe that all they really wanted to read about is how two extraordinary people made such an impact on my rather ordinary existence – and by doing so made me seem a touch extraordinary myself. I refer of course to my charismatic aunt, the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and my first cousin, the Queen, who in her Diamond Jubilee year is receiving the plaudits of the nation. Without them this book would have been as nothing. The book also coincided with the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton and a time of interest in and support for all the Royal Family.

The writing of this memoir started more years ago than I care to remember, simply as an account of my life to entertain my children and grandchildren, and now great grandchildren. Over the years one or two of my family told me ‘There could be a book in this, Mum’. I have to say I never believed them, but still added a few more pages to the yellowing pile beside my old-fashioned typewriter. Much more recently other people urged me to go public, believing that my story punctuates social history as I have lived it. I began, against my better judgement, the round of literary agents and publishers, being regularly rebuffed. It seemed that I was not in fashion, and I was often told: ‘It would be so easy if you were famous, like the wife of a footballer.’ But finally Umbria Press, to my delight, took the book on and those who turned me down have been proved wrong, while my family and supporters, against the odds, have been proved right.

Suddenly I really was a ‘celebrity’, with the book being serialised in the Mail on Sunday and Hello! It reached number one in the Sunday Times bestseller list, and has sold nearly 30,000 copies – ten times the first printing of 3,000 copies. I have been shuttled between newspaper and magazine offices, television and radio studios, to be interviewed about what I was doing, in say 1937 or 1945. The media, it seems, like living history, even an ancient monument like me. One reviewer had the cheek to suggest a preservation order should be slapped on me; surely I’m not that ancient. I’ve been very flattered by the reviews, but the one I particularly like remarked that my little book read as if a hostess were offering a string of amusing anecdotes to her dinner guests. That rather summed up my efforts, as I enormously enjoy entertaining and having people about me. It seems that I have caught the imagination of the book-reading public, and so the dinner party has turned into a rather large occasion. What else can I say, other than ‘Thank you so much for coming’.

CHAPTER ONE

The Final Curtsey

Saturday 30 March 2002 will be etched in my memory for ever, although it started like any other day at the Garden House, my home in the royal enclave in Windsor Great Park, which had been granted to me by my first cousin, the Queen, twenty-two years earlier. At that time, my husband Denys had become seriously ill and we thought it sensible to move from our isolated house on the edge of Dartmoor. The problem had been finding somewhere suitable and affordable. There was not a great deal of money in hand, and therefore I shall never forget the morning when my prayers were answered. I was out riding with the Queen on the Balmoral estate in Scotland and she suddenly turned in the saddle and said: ‘Could you bear to live in suburbia?’ It transpired that she was offering us a house in the Great Park at Windsor, the previous occupant of which had been the great horticulturist and landscaper Sir Eric Savill, the former Director of the Gardens in the Great Park, and architect of the famous Savill and Valley Gardens, which are close by.

Our new home was a short drive from the castle and almost round the corner from Royal Lodge, the weekend retreat of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, who was my mother’s youngest sister and my aunt. Royal Lodge had been her country retreat since 1932, after King George V gave it to his second son, then the Duke of York and his Duchess. This house was very special as far as Queen Elizabeth was concerned and she left her mark upon it. Together with her husband she shaped its grounds and gardens and they spent some of the happiest times of their lives there. Their work was guided by their neighbour Sir Eric Savill. It seemed to me absolutely appropriate that she spent the last weeks of her life there. The present Duke of York and his daughters Princesses Beatrice and Eugenie live in Royal Lodge now.

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother had been part of my life for as long as I could remember, and as the years passed she seemed immortal. She had, however, been unwell since Christmas 2001 and I suppose I had been steeling myself for the worst. But back to that March Saturday. It was sunny and bright and the usual chores, like exercising the dog had to be undertaken. Then about 11 o’clock the telephone rang. It was Sir Alistair Aird, my aunt’s Private Secretary, warning me that the end seemed close. She had been receiving regular visits from our local doctor, Jonathan Holliday, the Apothecary to the Household at Windsor, and on the morning of her death he was joined by Doctor Rich

ard Thompson, the Physician to the Queen. They concluded that she would not last the day.

I had just returned from a cruise with some friends down the Chilean coast and during that time Princess Margaret had died following a complete breakdown in her health. She had her third stroke on 8 February and developed cardiac problems. A few days before this she had told an old friend that she felt so ill that she longed to join her father, King George VI. My elder daughter Annabel had telephoned me on board the ship to break that sad news. Queen Elizabeth, although very frail, had bravely insisted on coming down from Sandringham, where she had been staying since Christmas, for her younger daughter’s funeral in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. After the funeral she returned home to Royal Lodge, and did not leave it again. I felt so sad about Margaret, but perhaps more for Queen Elizabeth than for anyone else. It is unnatural for a mother to suffer the death of a child, of whatever age, and it compounds the grief. Margaret, the Queen and I had grown up together and when young, Margaret had such great promise, beauty, intelligence and huge charm. It seemed a life unfulfilled in so many ways. In childhood, and when she was growing up, she was very indulged, especially by her father. If she did misbehave she invariably diffused the situation by making everyone laugh, so that the misdemeanour was forgotten, if not forgiven. It was hard to resist her, but she did have the most awful bad luck with men. However the Almighty usually gets the right people to be born first.

I arrived home at the Garden House on 3 March, and found that my aunt was still entertaining visitors. On 5 March she hosted a lawn meet and lunch for the Eton Beagles, and then held her usual house party for the Sandown Park Grand Military race meeting, but she weakened further in the week before Easter, which that year fell on 31 March.

Since 1991 I had been a Woman of the Bedchamber to my aunt, a mix of Lady-in-Waiting and companion, and in her final weeks I went to Royal Lodge every day, usually around 11 or 12, and had lunch with her, the meal being set on a card table in the drawing room. I tried to amuse her with snippets of news that might interest her. It was difficult to get her to eat much. About all she could usually manage was a cup of soup, although her Chef, her Page, and I spent a lot of time trying to think of dishes that might tempt her. But it was wonderful to see her every day, and I would take her little bunches of early daffodils and primroses; any flower that was really sweet smelling. I loved her so much, and I like to think that she regarded me as her third daughter, once paying me the compliment of introducing me as such to a visiting Scandinavian monarch.

The days passed in this fashion until that telephone call. As I arrived at Royal Lodge I saw that the Queen’s car was there. I went straight to my aunt’s bedroom and found her sitting in her armchair. The Queen was beside her, wearing riding clothes. She had been alerted while riding in the Park; her groom always carrying a radio link to the castle. The nurse from the local surgery and my aunt’s Dresser — or Royal Household speak for Ladies’ Maid — were also there. My aunt’s eyes were shut and thereafter she did not open them or speak another word. The doctors came and went, but the nurse, the Dresser and I stayed throughout. John Ovenden, the Parish Priest of the Royal Chapel, Windsor Great Park, arrived and went straight into Queen Elizabeth’s bedroom. He knelt by my aunt’s chair, holding her hand and praying quietly. He also recited a Highland lament: ‘I am going now into the sleep . . .’ He later told me that he was sure she knew what was happening, because she squeezed his hand. She was 101 – such a very great age. She had arrived in the time of horse-drawn carriages and was leaving it having seen men walking on the moon.

After a while I was persuaded to take a break and went for a walk in the garden. When I came back she had been put to bed. She looked so peaceful. At her bedside was the Queen, accompanied by Princess Margaret’s children, David Linley and Sarah Chatto. John Ovenden also came back, and we all stood round the bed when he said the prayer: ‘Now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.’ We all had tears in our eyes and to this day I cannot hear that being said without wanting to cry. Queen Elizabeth died at 3.15 in the afternoon on 30 March 2002. She just slipped away and her death certificate said that the cause of death was ‘extreme old age’. I returned home soon after, thinking that it was strangely significant that she had died on Easter Saturday, the day before the Resurrection. It had been a long and emotionally exhausting day, and I was so touched when David Linley telephoned to say that the Queen would like me to spend the night at the castle.

That evening passed in rather a blur. We had dinner and talked about more or less normal things. We went to bed quite early and next morning we attended communion in the Castle chapel. Later I went to Matins in the Park chapel, and then drove over to Royal Lodge, to make sure all was well with the staff. The Dresser asked me if I would like to see my aunt. She looked lovely and almost younger, death having wiped the lines away. I knelt by her bed and said a prayer for her.

Then I stood up and gave her my final curtsey.

* * *

Later, I was deputed to register my aunt’s death at the Windsor Registrar’s office. I was shown into the room of a rather fierce-looking lady and we went through the formalities while she ticked the relevant boxes.

At a certain point, she fixed me with a beady eye and asked, ‘Right, what was the husband’s occupation?’ It seemed a superfluous question; however, after a second’s hesitation, I answered, ‘King’. I think Queen Elizabeth might have found that almost amusing.

CHAPTER TWO

Upstairs and Downstairs

It seems strange that I once lived in what would turn out to be the last days of a long lost world of seemingly unassailable privilege. Although when it is happening it all seems perfectly normal — especially to a small child as I was. The First World War signalled the threatening clouds and the death throes had done their deed by the end of the Second World War. In the year of my birth — 1925 — the Charleston hit town, and twelve months later the General Strike generated a class war that almost split Britain. The TUC had called out the workers, but the impact did not reach the middle of Scotland. My mother was still receiving the cook every morning to discuss the day’s menus. The staff ate in two separate dining rooms, one for the senior members such as the butler, housekeeper, ladies’ maid and the head housemaid. If there were visiting valets or ladies’ maids, they were included. All the other staff ate together in another room, as in the television series ‘Downton Abbey’. Before the war, in many grand houses, lady guests would be expected to change clothes three times a day, from morning dress to afternoon dress, and finally long evening dress, with decorations and tiaras. The housemaids had to conform as well, wearing some sort of white overall outfit in the mornings, when all the heavy cleaning was done, and black dresses with little white aprons, rather like the uniform once worn by the waitresses in Lyons Corner Houses — they were called ‘Nippies’ — in the afternoon and evening.

When Queen Mary came to stay with my family, I was given strict instructions by my mother on the required protocol. This entailed kissing her on the cheek, followed by kissing her hand and then curtseying. Of course, I muddled it up, getting it all in the wrong order, finally rising from my obeisance to biff Her Majesty under the chin with the top of my head, as her face lent forward to receive a kiss, which I had forgotten. Luckily this misadventure did not ruffle the calm of the grand old lady. Later in the same year King George II of Greece arrived and I curtseyed deeply to his imposing equerry and shook hands firmly with the King. How was I to know which was which.

Silly games were often played by the grown-ups and enjoyed by spectators, such as ‘Are you there Moriarty?’ Two people, blindfolded, lie on the ground with cushions, trying to hit each other when they answer.

There were many other, more light-hearted family occasions, when my aunt, the Duchess of York and her husband, with the two Princesses, visited us. They played some pretty odd and boisterous games, with distinguished visitors rolling round on the ground being beaten round the head with cu

shions or with newspapers which had been folded into batons, playing the game known as ‘Are you there, Moriarty?’ We three girls were surprised at the curious goings on of the grown-ups.

Cocooned in the nursery I, of course, knew nothing about the social convulsions gripping the country, and neither did my first cousin, Princess Elizabeth, who was born a year after I was in 1926, that tumultuous strike year, just thirteen days before the mass walk outs started. I learned very much later that her father, then Duke of York, and after the abdication of King Edward VIII, King George VI, was intensely worried about the crisis, and frustrated because his position prevented him from offering any advice, despite his knowledge of industrial affairs and his deep interest in the welfare of working men and women. He was President of the Industrial Welfare Society, and, when asked whether he wanted to take the job on, typically said: ‘I’ll do it provided there’s no damned red carpet about it’.

My father, the 16th Lord Elphinstone

May, my mother – gardening as usual

His personal contribution to breaking down social barriers was through his camps, at which thousands of boys aged between seventeen and nineteen, from widely differing backgrounds, mixed, worked, and played together. He came to be known as ‘the Industrial Prince’ and, sometimes less kindly by his brothers as ‘the Foreman’.

My father, the 16th Lord Elphinstone, was born in 1869. For some odd reason I was rather proud that he had come into the world exactly halfway through Queen Victoria’s long reign. I love facts that telescope history. For instance my father’s sister had a Godmother who was married to one of Napoleon’s ADCs, the Comte de Flahaut, who was the illegitimate son of that great survivor of revolutions, Talleyrand, bishop and turncoat aristocrat, who somehow dodged the guillotine and always managed to end up on the winning side. I have quite lately discovered what I think is a fascinating historical fact. When the Queen visited Normandy recently, she was met with cries of ‘Vive le Duc’, as if she were the living embodiment of the Duke who invaded us in 1066.

The Final Curtsey

The Final Curtsey